沉积岩风化排放的碳还能进入河流乃至海洋中[

尽管全球碳通量研究很重要,但对沉积岩风化向大气中排放CO2的气候敏感性仍不清楚。尤其是OCpetro,一直认为它在风化带(weathering zone)中不是很活跃且不易被氧化[12]。以前对岩石风化排放CO2的相关认识,主要来自于对河水中可溶性地球化学示踪剂的研究[13-14]。这些研究强调了物理侵蚀在影响CO2排放速率方面的重要角色,这里的侵蚀作用为近表层的氧化风化作用补给了大量的OCpetro和硫化物矿物[15]。然而,这些评估结果在流域上做了平均处理,同时综合了不同水文和温度条件下的化学反应。比如,近来研究强调了“历史时期山地河流中硫酸盐通量的增加趋势可能反映了硫化物氧化对气候变暖的响应”,但缺乏直接证据[16]。

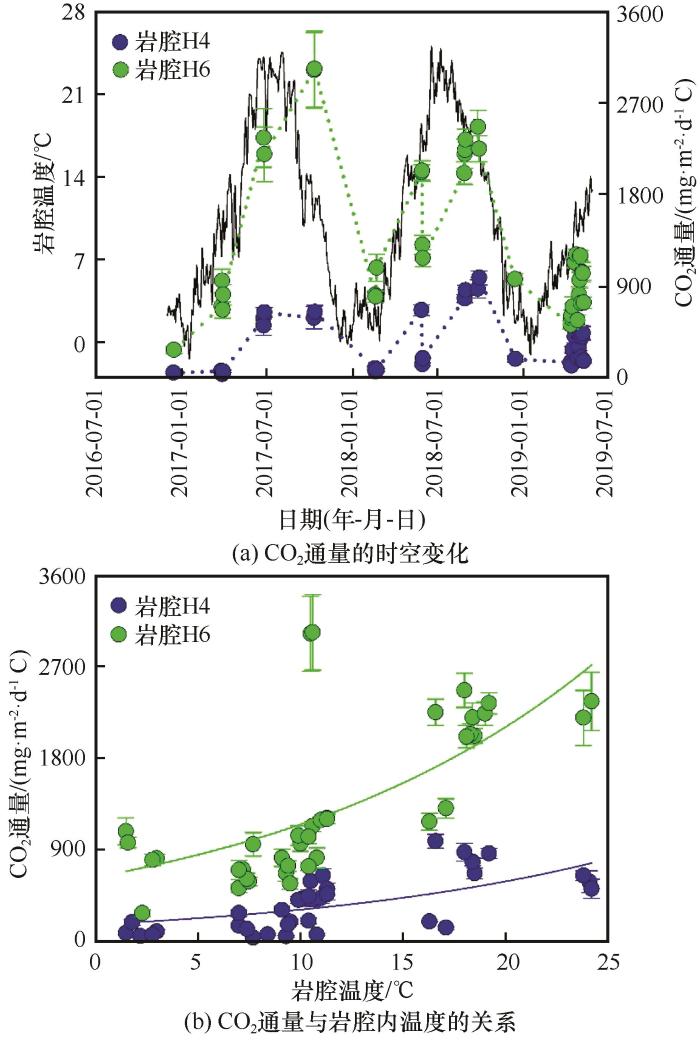

近期发表在Nature Geoscience的研究指出,沉积岩风化对全球变暖是正反馈,在整个地球历史中可能一直驱动着地表碳循环[1]。具体来说,在2016年12月至2019年5月的两年多时间内,Soulet等[17]连续监测了法国Laval流域沉积岩岩腔(rock chambers)内CO2排放的季节变化过程;通过沸石分子筛(zeolite molecular sieves)和活性CO2捕获法(trapping method)采集岩石风化排放的CO2,通过测定排放的CO2的稳定性及放射性碳同位素来识别CO2的具体来源。结果指出,沉积岩风化排放的CO2来自黄铁矿氧化耦合碳酸盐溶解作用[式(

图1

这项研究向模拟化学风化与碳循环的地质碳循环模型提出了挑战。长期以来,认为岩石化学风化对气候变化是一种负反馈,即在大气CO2溶于水生成的碳酸作用下硅酸盐风化会促进大气CO2的地质封存,这种封存能力会随着大气CO2浓度的增加而增强[21]。据估计,全球大气CO2的地质封存量为90~120 MtC·a-1[1],而在以沉积岩为主的陆地表面OCpetro的氧化速率为40~100 MtC·a-1[9],二者的碳源汇作用基本相当。OCpetro氧化的CO2排放量可能主要受低至中等热成熟度(thermal maturity)的页岩风化作用影响[9],页岩的OCpetro含量类似于Laval流域的岩石,与更高等级的变质岩不同[22]。与Laval流域的研究类似,物理侵蚀作用很可能加快了全球OCpetro的氧化速率[3,14]。然而,在有深部风化前缘(weathering fronts)的低剥蚀速率地区,温度对岩石风化源CO2通量的影响还需进一步研究[1,23]。

如果将Soulet等[1]的研究结果外推,全球温度增加2~4 ℃会使来自OCpetro氧化的CO2排放量增加15%~30%。然而,这种在地质时间尺度上CO2排放的不平衡性不可能持续大约10万年以上,因此需要重新研究岩石化学风化在气候调节方面的作用机制[21,24]。在全球尺度上,对沉积岩中硫化物和碳酸盐矿物的共存特征,以及硫化物耦合碳酸盐风化的CO2排放量都知之甚少[13],这可能进一步增强了与OCpetro氧化风化有关的对大气CO2浓度的正反馈作用[1]。总之,沉积岩风化对气候变化是正反馈,这在以前的研究中被忽视了,而且当前的地质碳循环模型还没有捕捉到受控于温度的OCpetro氧化以及硫酸溶解碳酸钙的CO2排放过程[1,25],因此未来的岩石风化与碳循环研究应将沉积岩风化的温度敏感性与硅酸盐风化一起考虑[1]。

参考文献

Temperature control on CO2 emissions from the weathering of sedimentary rocks

[J].

Mountains, erosion and the carbon cycle

[J].

Soil respiration and georespiration distinguished by transport analyses of vadose CO2, 13CO2, and 14CO2

[J].

Sulphide oxidation and carbonate dissolution as a source of CO2 over geological timescales

[J].

The role of sulfur in chemical weathering and atmospheric CO2 fluxes: evidence from major ions, δ 13CDIC, and δ 34SSO4 in rivers of the Canadian Cordillera

[J].

The new global lithological map database GLiM: a representation of rock properties at the Earth surface

[J].

Storage and release of fossil organic carbon related to weathering of sedimentary rocks

[J].

Sulfur isotopes in rivers: Insights into global weathering budgets, pyrite oxidation, and the modern sulfur cycle

[J].

Sedimentary organic matter preservation: an assessment and speculative synthesis

[J].

Glacial weathering, sulfide oxidation, and global carbon cycle feedbacks

[J].

Mountain glaciation drives rapid oxidation of rock-bound organic carbon

[J].

Co-variation of silicate, carbonate and sulfide weathering drives CO2 release with erosion

[J].

Evidence for accelerated weathering and sulfate export in high alpine environments

[J].

In situ measurement of flux and isotopic composition of CO2 released during oxidative weathering of sedimentary rocks

[J].

Greenhouse gas emissions from soils: a review

[J].

Probing deep weathering in the Shale Hills Critical Zone Observatory, Pennsylvania (USA): the hypothesis of nested chemical reaction fronts in the subsurface

[J].

Response of net ecosystem CO2 exchange to precipitation events in the Badain Jaran Desert

[J].

Hydrologic regulation of chemical weathering and the geologic carbon cycle

[J].

Recycling of graphite during Himalayan erosion: a geological stabilization of carbon in the crust

[J].

Deep abiotic weathering of pyrite

[J].

The need for mass balance and feedback in the geochemical carbon cycle

[J].

Neogene cooling driven by land surface reactivity rather than increased weathering fluxes

[J].

甘公网安备 62010202000676号

甘公网安备 62010202000676号